I see this play out constantly: procurement teams deliver strong results and hit their targets for the business. Somehow, their CFO is still disappointed.

The part that stings? It's usually procurement's fault. And it stems from not using spend data to set proper expectations with stakeholders upfront.

Let’s dig into this mistake and the fix through the lens of a common hypothetical scenario:

Meet Arnold, a procurement director who just closed Q4 with $1M in savings against a $1M goal. His CFO was thrilled. So thrilled, in fact, that she immediately raised the Q1 target to $1.2M. Arnold's team, eager to maintain momentum, jumped on it. They pushed hard in negotiations, over-delivered on a few big projects, and by quarter's end had generated $850K in savings.

Arnold was exhausted. His team was burned out. And his CFO? Not happy.

The Mistake? Flying Blind on Optimism

Arnold's problem wasn't that he underperformed. His problem was that he said yes to a goal without checking if the pipeline (demand) could support it.

Here's what happens in most organizations: Q4 is heavy with year-end purchasing, budget flushes, and renewals that got pushed from earlier quarters. Then Q1 arrives - lighter on contracts, cautious on new spend, and some percentage chunk smaller in total addressable dollars. But somehow, the savings target went up 20%.

And leaning on just that historical trend is not enough. Before committing to a new savings target, Arnold should have conducted a simple spend analysis to gain alignment with his CFO up front. By doing so, he would’ve gotten a clearer picture of two important things:

- How dollars are being spent

- Where dollars are headed

When Arnold committed to that $1.2M goal, he was operating on optimism instead of data. He didn't know that his Q1 pipeline would include only $4.3M in expiring contracts and $2.9M in budgeted new spend – a fraction of what Q4 offered. He couldn't see that even maintaining his team's impressive savings rates from the prior quarter would only yield about $810K.

Your CFO isn't setting you up to fail. But without transparency into what's actually coming through the pipeline, you're setting yourself up to look like you are.

Overall, the fix looks like this:

- Dig into your spend pipeline

- Provide an updated forecast

- Determine options and let your stakeholder decide

Dig Into Your Spend Pipeline (3 Elements That Live in There)

Spend visibility - understanding the composition and volume of your current and future spend - is foundational. You can't control what you can't see.

Your spend pipeline consists of three buckets, and each behaves differently:

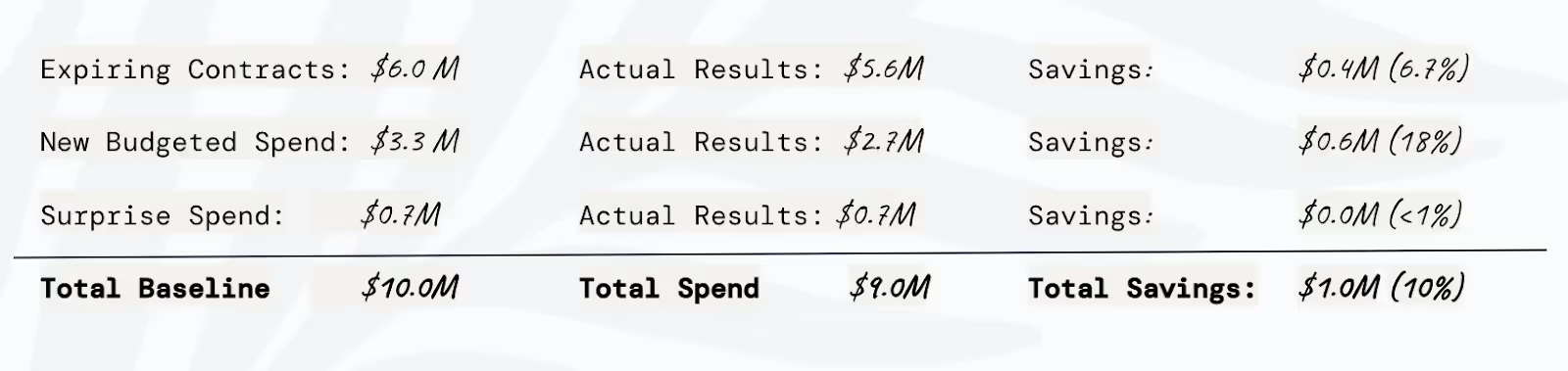

- Expiring contracts getting replaced by a new contract: These are either with the incumbent or competitive replacement. You know they're coming, you can plan for them, and historically, they offer moderate savings potential. In Arnold's Q4, these contracts averaged 6.7% savings against baseline.

- New budgeted/approved spend: These are tools and services your business has approved and allocated budget for. They're net-new purchases, which means you have more leverage to negotiate since you're not locked into an incumbent. Arnold's team achieved 18% average savings on new spend in Q4.

- Possible surprise spend: This is the unplanned, urgent, "we need this yesterday" spending that bypasses your normal process. It offers almost zero savings opportunity because there's no time to source alternatives or negotiate properly. Arnold's surprise spend in Q4? Less than 1% savings.

Here's what Arnold's total spend in Q4 looked like when he broke down the numbers:

Forecasted spend was $9.3M, but baseline climbed to $10.0M with unplanned additions. Arnold's team reduced actual spend to $9.0M, generating that $1M in savings.

Great quarter. But Q1 wasn't going to be Q4. Spend analysis means understanding not just where your money went, but where it's going and what levers you'll have when it gets there.

Provide Updated Forecast and Savings Target

Once you understand your pipeline, you can forecast with precision instead of hope. Arnold needed three numbers to know whether his CFO's $1.2M goal was achievable:

- Your actual demand pipeline: This is the total spend you'll have the opportunity to influence in the coming quarter. For Arnold's Q1, this was $4.3M in expiring contracts plus $2.9M in new budgeted spend - a total of $7.2M. That's 28% less than Q4's $10M baseline.

- Your realistic savings percentage: This isn't aspirational. It's what you've actually achieved historically, broken down by spend category. Arnold's team averaged 6.7% on renewals and 18% on new spend in Q4. There's no reason to assume Q1 would be dramatically different.

- Your surprise spend buffer: This is the wildcard spending you can't predict but should account for. It historically delivers near-zero savings, but it's part of the reality of operating a business. Arnold should have assumed some percentage of surprise spend would materialize.

Here's what Arnold's realistic Q1 forecast should have looked like:

Applying those same historical savings rates to a smaller pipeline: $810K in projected savings. Not $1.2M. With this number, Arnold's actual Q1 performance of $850K would have exceeded expectations by 5% instead of falling short by 29%.

Notice the shift?

Determine Options and Let Your CFO Decide

Having the data is half the battle. The other half is knowing exactly what to do with it.

This is where most procurement teams stumble. They gather the numbers, realize the goal is unrealistic, and either stay silent (hoping they'll somehow pull off a miracle) or complain that the target is unfair (which makes them look defensive). Neither approach elevates your credibility.

Here’s a better way: Don't just show the data. Use the data to present options and put your stakeholder in the driver's seat.

When Arnold's CFO proposed that $1.2M goal, Arnold should have responded with data from his spend analysis:

"Before we finalize Q1 goals, I want to show you what I'm seeing in our spend pipeline. We have $4.3M in expiring contracts and $2.9M in budgeted new spend coming through Q1. In Q4, we averaged 6.7% savings on renewals and 18% on new purchases. If we maintain those rates, we're looking at about $810K in realistic savings - not $1.2M."

Then comes the critical move. Instead of stopping there, present the options:

"That said, we have two paths forward. Option one: We keep the $810K target as our baseline and call anything above that a stretch win. Option two: If hitting $1.2M is critical, we can explore additional levers - maybe accelerating some Q2 renewals into Q1, or looking at opportunities to switch suppliers where we've historically just renewed. But that would require more bandwidth from my team and earlier visibility into budget decisions. Based on this data, how would you like me to proceed?"

You've just done something powerful. You've shown that you understand the business reality, you respect your CFO's goals, and you're not afraid to surface trade-offs. Most importantly, you've given her agency to make an informed decision instead of forcing her to react to a shortfall later.

Another Example: What This Looks Like in Real Time

I’ve employed this technique in a recent negotiation. I understood that the stakeholder had a tight budget of about $40K. I also had data that suggested that I might be able to get an impressive 50% discount with the current supplier if I leveraged all my negotiation techniques. The problem is that even with this discount, we’d still be over budget by about $10K given the supplier’s annual uplifts.

With that intel, here are the possible options the company could take:

Option A: Look at other suppliers to stay under the $40K budget

While it’s important to source and find the right features for your needs, it’s equally important to consider migration fees and time when transitioning to a new provider. Investigate questions like:

- How is the service level compared to the current supplier?

- How long does onboarding and training take?

- Does my team have the bandwidth to onboard, learn, and train a new system?

Option B: Stay with the incumbent solution but end up $10-15K over budget

Make it clear to your stakeholder that staying with the incumbent solution means you will be over budget regardless of any discounts you may be able to negotiate. Often this will become a conversation about how much your team is using this tool and whether or not features fit needs. Investigate questions like:

- What are utilization rates in the past X months for this tool?

- Does my team enjoy using this tool? Anything that could make it better?

Without setting expectations appropriately, I might have returned with my 50% discount only to have the stakeholder say something like, “I don’t know, it’s still above budget. Maybe I should have just negotiated myself.”

Here’s how I presented both options and put her in the driver’s seat:

“Look, I’ve benchmarked XYZ solution and talked to several other customers. Check out this data: It shows that a 50% discount would be a very impressive feat, but 40% is much more likely. Even with these discounts, we’d still end up over budget. So we can either look at other providers if you really need to get down to that $40K budget OR stay with the incumbent but still end up $10-15K above your budget.”

I proceeded to explain that I did some initial research and found that competitor XYZ could likely achieve our cost goal but tends to have a lower service level. Additionally, the transition would take about 6 weeks and require a sizable chunk of time from at least 2 of your team members. Then I asked the stakeholder: “Based on this data, how would you like me to proceed?”

After mulling it over, the stakeholder said, “You know the team has been through a lot of change recently and they really like this tool. We think it will deliver higher ROI. What I heard you say is that a 40% discount with the incumbent is likely but a 50% might be possible. It would mean a lot if you can do everything you can to achieve the 50% discount and I’ll go to finance to try and work out the difference.”

The Compounding Effect

Few things in procurement are more frustrating than being underappreciated for your effort. You negotiate hard, deliver results, and still get treated like a back-office cost center.

But you can't blame the CFO if you haven't set proper expectations.

Reality is that two procurement professionals can achieve identical savings. Yet, one is perceived as a strategic partner; the other is seen as someone who chronically underdelivers. The difference is mostly always communication.

The professional who uses data to set expectations upfront, who presents options instead of just reporting outcomes, and who treats their CFO as a partner in decision-making rather than someone to report to - that person changes the dynamic permanently.

When Arnold goes into Q2 with a data-backed forecast, shows his CFO where the opportunities and constraints are, and involves her in prioritizing which negotiations matter most, something shifts. She starts engaging with him earlier. She starts asking his opinion before making budget decisions. She starts defending procurement's value to the executive team.

This compounds. By Q3, Arnold is now shaping the savings targets with the finance team. By Q4, he's presenting the annual procurement strategy and getting buy-in on multi-quarter initiatives that require upfront investment but deliver significant long-term savings.

That's what data does. It repositions procurement from order-taker to strategic partner.

Related blogs

Discover why hundreds of companies choose Tropic to gain visibility and control of their spend.

.avif)